Lessons learned from The Constellation experience in India between March 2017 and June 2020

Introduction

The Constellation worked in Assam between March 2017 and June 2019. It worked in Shimla and Udaipur between April 2019 and June 2020. These projects helped The Constellation to understand how to evaluate of the impact of its work. This note discusses how we can use that understanding to evaluate our work in the future.

The Projects

Phase 1 of the Assam Project began in April 2017 and finished in April 2018. The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) funded the work. Our project was one of a group that explored innovative ways to increase the uptake of immunisation. The aim of the Assam project was to explore the impact of the SALT approach on the take-up of immunisation. The Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) carried out an Impact Evaluation of the programme. Their evaluation showed that the intervention had an insignificant impact on the uptake of immunisation in the 90 targeted villages.

Phase 2 of the Assam Project began in May 2018 and finished in May 2019. The Trust for Local Response funded the work. The Project covered the same 90 villages that took part in Phase 1 . However, the communities now identified issues and defined actions based on their priorities and schedules. In this sense, Phase 2 was a normal The Constellation project.

The Medtronic Transition Project followed encouraging results from an experiment using the SALT approach within the HealthRise program in Shimla and Udaipur. HealthRise is a 5-year multi-country program, supported by Medtronic Foundation, that seeks to reduce premature mortality associated with NCDs. The SALT experiment found improved adherence to treatment among a small sample of patients. This led to the Medtronic Transition Project to explore these finding further with a larger sample. The target population for the Transition Project came from HealthRise enrolled patients diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension aged between 18 and 70.

The idea of Impact Assessment

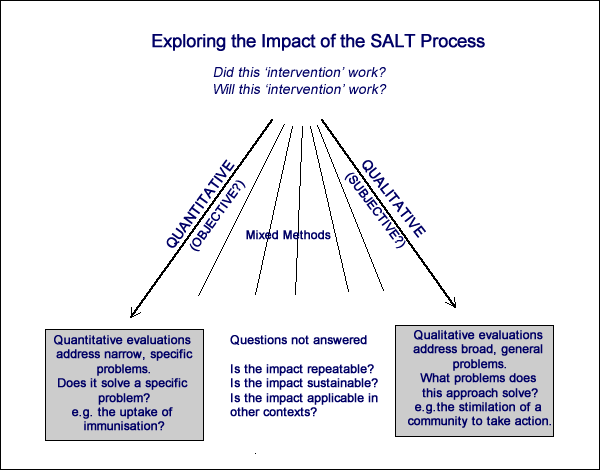

The purpose of Impact Assessment is to understand if an ‘intervention’ did work to provide confidence that a new ‘intervention’ will work. An assessment can be either quantitative, qualitative or a combination of qualitative and quantitative (‘mixed methods’). With a quantitative approach, a narrow and specific question produces a binary answer. With a qualitative approach, we are not restricted to a binary answer and broader questions can be explored. It is possible to use either approach to support the other.

Phase 1 of the Assam Project was a quantitative study that provided a specific answer to a specific question. Phase 2 of the Assam Project was a qualitative study that explored a diverse range of responses to the SALT approach. The Medtronic Transition Project was a quantitative study supported by qualitative methods.

Assam Phase 1 (March 2018 to June 2018)

This was a sophisticated quantitative exploration conducted by PHFI. (LINK) The question that the study addressed was clear and specific. It showed that over a 12-month period the SALT approach did not increase the uptake of immunisation.

The most important lesson from our work in Assam is that our approach brings an inevitable tension when the external objective (increasing the level of immunisation) does not have an equal priority with the community that is being invited to own that objective. We recognised this tension from the start. We rationalised that if we framed the project as being about ‘Healthy Children’ then we could square this circle. With some communities this worked out: in many others, it was always clear that immunisation was never going to be a high priority. We saw the tensions throughout the project in a variety of ways. There is a real doubt in our minds whether our approach was suited to the objective.

Assam Phase 2 (May 2018 to May 2019)

As we reached the end of Phase 1, we felt that we were leaving with our work incomplete. The confidence of the facilitators was growing and the communities were coming to understand that they could take action. We raised funds to work with the same facilitators in the same villages for a further year. We returned to our usual way of working: the community identified the issues that were important to them and defined action plans based on their own priorities. Some communities continued to prioritise immunisation, while others had different priorities.

We understood that to explore the impact of the SALT approach in this situation we needed to ask broader, more general questions. We decided to use the Outcome Harvesting. With this qualitative methodology, we seek to understand the impact of the actions that the community has chosen. As with so many other issues, the COVID pandemic meant that this study was more difficult and took more time and we still await the final report.

However, the interim evaluation reported: “The project showed a clear effect on various tangible issues, primarily water cleanliness, cleanliness and sanitation, immunization, nutrition, quality of education, and school dropout. While immunization was the main entry point for the project to address issues in the villages, it clearly also was able to raise awareness of a few other issues. In some villages, even some culturally more challenging issues such as child marriage were about to be addressed.”

“Another strength of the approach is that is enables villages to create a linkage to existing schemes. In Kamrup, for example, a village was able to connect the school to the public water supply in order to ensure safe drinking water. In other villages, the community leaders had started to contact the government regarding the construction of public roads.”

“The utility of the project to instil and sustain behavioural changes is striking and unprecedented. While this effect cannot be measured in numbers, it becomes visible when young girls take the floor in front of the whole community or when fathers take their children to the vaccination appointments.”

The Medtronic Transition Project (May 2019 to June 2020)

Our challenge in Assam Phase 1 was that the objective of the funder was not congruent with the that of the communities. In contrast, this alignment was present in the Medtronic Transition Project. The target group for the programme were patients diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension between 18 and 70 years of age. Participants faced a clear challenge and they had the capacity to influence change both as individuals and as members of communities. The programme was designed to explore both quantitative and qualitative lifestyle changes and medical outcomes. It was truly unfortunate that both the implementation and evaluation of the Transition Project were so severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, the results from the project were very encouraging.

Overall, most of the lifestyle behaviours of the study participants significantly improved from baseline to end-line evaluations in Shimla and Udaipur in the old CLCP [patients enrolled in the first project] and the new CLCP study arms which sheds light on the behaviour changes after the SALT-CLCP methodology was implemented.

Conclusion

The three projects covered in this note cover a long and difficult journey that had deepened our understanding of the evaluation process. We believe that we capture the essence of what we have learned with the word ‘congruence’. We do not believe that any specific approach or methodology is better or worse than another. It is necessary to ensure that the project objective, the methodology used in the project and the evaluation methodology are congruent. This means that all three aspects must be considered at the design stage and during the implementation.

The ideal, the spirit and the challenge of the SALT approach was captured beautifully by the programme officer from C-NES, the Assamese NGO that worked with The Constellation in Assam. He thought that the capacity-building and ownership process of the community in the SALT approach was ‘very good’. He added that one year was not sufficient for SALT, as people now had started seeing change and were coming forward to be SALT champions; and that sustaining changes might require the process to continue for one or two more years or longer.

“I don’t want to claim that we have fulfilled everything. No doubt the SALT process is a beautiful one but not easy at all. Essentially it is an antithesis of the age-old tradition that people at large [have been] accustomed to for so long. For example, to appreciate, to arrange a meeting, get together, to discuss with the community, generally we lack these qualities. Those qualities are being developed to a great extent. Yes, obviously it will sustain, if we can increase the longevity of the SALT process by a few more years. It will take some time. Mere one or two years may not be enough. We cannot expect such a good thing within a short span of time. But we are sure that if the same pace continues then obviously the day will not be very far when [the] SALT process will be [one] hundred per cent successful.”

We should carry this insight with us whenever we seek to design, to implement or to evaluate one of our projects.